Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt

The Nobel Peace Prize 1906

After camping in Yosemite National Park, “It was like lying in a great solemn cathedral, far vaster and more beautiful than any built by man.”

Biography

Treaty, Portsmouth

Biographical Books

Books

Papers

Humor/Quotations

Images

Honoring Roosevelt

Video/Films

Death

Health

Nobel Prize Cash and Philanthropy

Peace in the East

Theodore Roosevelt and The Treaty of Portsmouth

By Jon Curran

Abstract

President Theodore Roosevelt became America’s first Noble Peace Prize winner for his efforts in bringing an end to the first conventional war of the 20th century, the Russo-Japanese war between Russia and Japan. Peace negotiations took place in Portsmouth, New Hampshire between August and September of 1905. Some critics have been quick to point out that Roosevelt was not in Portsmouth for the negotiations, suggesting that fact diminishes his role in the peace talks (Tønnesson Controversies and criticisms). This report will examine details of events surrounding the Treaty of Portsmouth and Roosevelt’s leadership in it.

Background

Russo-Japanese War

After centuries of isolationism Japan in 1904, only recently industrialized, competed with Russia for greater influence in Asia. War started with a surprise Japanese attack on Russian-controlled Port Arthur which eventually fell to Japan. Japan continued to have victories over Russia and became the first Asian power to overcome a western power (Hunter Russo-Japanese War). Despite Russian losses, Tsar Nicholas maintained that Russian would prevail, evading peace negotiations. The Russian leader believed Russia he had a “Holy Mission” to influence the Pacific region and may have had a hostile opinion of the Japanese due to an incident as a young adult. A 22-year-old Nicholas embarked on a grand tour of Europe and the Orient, but his trip was cut short after he was attacked by a Japanese policeman wielding a sword while visiting Japan. The incident left a permanent scar on his head (Randall and Doleac People, Part Three).

World Peace in the Balance

The Russo-Japanese War increased tensions between countries in Europe. Britain, France, Germany, and Italy all had different interests in Asia and developed alliances with differing sides. A prolonged war threatened to bring war to Europe (Randall and Doleac Intro) (Randall and Doleac War, Part Six).

Roosevelt and Kaneko

The United States was officially neutral regarding the conflict. Yet President Theodore Roosevelt had several informal meetings with friend and former Harvard classmate Kaneko Kentarō, who was part of a special Japanese diplomatic envoy to foster Japanese sympathy in America. Kaneko conducted many speaking lectures and informal interactions with the President. In an early meeting, Roosevelt asked Kaneko for a book to help him understand the Japanese people and cultural. Kaneko gave him “Bushido: The Soul of Japan” (Matsumura, Masayoshi. Nichi-Ro senso to Kaneko Kentaro). Roosevelt increasingly became more eager to facilitate peace between Russia and Japan but understood it would be difficult so long as Tsar Nicholas believed there was a chance that Russia could prevail. Russia’s war strategy was to send their Baltic Naval Fleet 18,000 miles to reinforce Russian troops and cut off the Japanese Army in Manchuria from the Japan island homeland (Randall and Doleac War, Part Five). Theodore Roosevelt, a navel historian and strategist and formal Assistant Secretary to the Navy, gave Kaneko strategies for the upcoming naval battle between Japan and Russia (Nakanishi 76). Roosevelt feared that Japanese Admiral Togo Heihachiro might use the classic “crossing the T” maneuver with his fleet and advised against it. Crossing the T would align the Japanese ships perpendicular to the approaching Russian convoy. Roosevelt’s concern was that the Russians would simply cut through the middle of the defending line and continue to the safety of Vladivostok; where they would reinforce the Russian army and gain a naval foothold in the region. Roosevelt understood that a Japanese victory meant preventing the Russian fleet from reaching Valdivostok. The Russians had two options in the approaching battle, evade the Japanese navy or to defeat the Japanese navy. The Japanese had to defeat the Russian navy. Thus, if the “crossing the T” formation was used, it was plausible that the Russians would simply use the speed of their ships to cut through the battle line formation and evade a prolonged battle (Nakanishi 84). Defeating the Russian navy was essential to create the opportunity for peace talks. The President deployed US warships to the Tsushima Straits to deter any currently neutral nations from entering the battle (Nakanishi 75-76).

The Battle of Tsushima

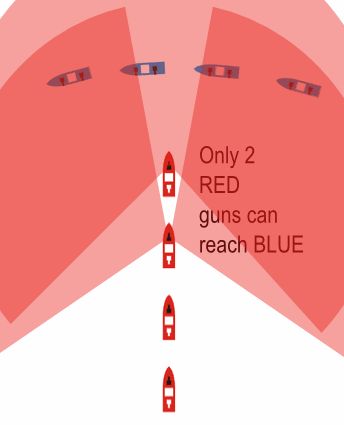

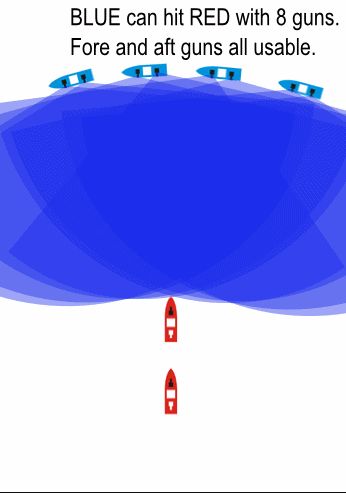

Leading up to the battle there was ongoing debates with Admiral Togo and his staff whether to engage the Russians by “crossing the T” (Nakanishi 84). The benefits of the classic strategy is that that the crossing ship can shoot with all of their turrets shooting at the approaching enemy while the approaching ship can only use their front turrets and will have much their line of sight obstructed by friendly ships (Hughes, Wayne P. Fleet tactics and coastal combat).

Though it has been widely stated that Admiral Togo employed “crossing the T”, according to Japanese Veteran Rear Admiral Yoichi Hiraina, Togo really employed a rotating attack similar to the Kuruma Gakari formation used in Japanese medieval battles, with the objective to bring the Russian fleet to battle (World of Warships Naval Legends: Battle of Tsushima). The formation was semicircular not perpendicular, reversing direction at one end by turning in sequence. Thought this strategy left the Japanese fleet significantly more vulnerable to Russian fire versus a classic T, it resulted in creating a formal battle pitch to engage the Russian fleet and a second line moving in a reverse direction queued to engage any Russian ships trying to break through to Valdivostok (Killarnee Battle of Tsushima).

Kaneko received a telegram at his hotel on May 27th, 1905 that stated that the Russian and Japanese engaged in Tsushima Straits; it reported that six Russian ships were sank, nine captured, and no Japanese were hurt. Though jubilant, Kaneko needlessly feared the news was too good to be true. Of the 38 Russian ships only three elevated destruction or capture; Japan lost only three torpedo boats (Nakanishi 75-76, 84).

Peace Talks

The Start

On May 31, 1905 Japan secretly asked Roosevelt to mediate peace. Though initially reluctant to peace Tsar Nicholas realized the war was unpopular, hurting Russia’s fragile economy, depleting Russia’s treasury, and threatened to spark a revolution to overthrow his government. He agreed to peace talks, so long at the talks were initiated by Roosevelt and not by Japan. On June 7th Roosevelt extended a formal offer to mediate the end of the war, and both sides agreed to the talks on June 12th (Randall and Doleac War, Part Six). The same day that President Roosevelt extended his offer to mediate the peace, he met with Kaneko at the White House. Roosevelt told Kaneko that Japan should send 2 army corps and 2 battleships to occupy Sakhalin Island (Nakanishi 76). Sakhalin Island was taken from Japan in the 1850s then officially cited to Russia by Japan in 1875 (G. Patrick March Eastern Destiny: Russia in Asia and the North Pacific) (Randall and Doleac War, Part Six).

Roosevelt and Kaneko discussed the location of the peace talks. Shying away from prominence, Roosevelt suggested The Hauge, Netherlands instead of the United States. Kaneko was insistent that Roosevelt should receive glory for his work to bring peace stating, “George Washington and Abraham Lincoln are great in American history and everyone knows them. But they were not international figures. This is a chance for the United States to be known as an international mediator for peace. Even though it will be a direct negotiation between the two delegates, I think that America is best suited, and as a friend I want you to have the honor” (Nakanishi 76-77). Roosevelt selected Portsmouth, New Hampshire for is cooler climate. Talks in Washington, DC during August would be sweltering and would inhibit conciliation (Randall and Doleac Place, Part three).

One day prior the Japanese negotiators departure to the peace conference, the Japanese reoccupied Sakhalin Island; securing a bargaining chip for the negotiations (Randall and Doleac War, Part Six).

Sagamore Hill; Oyster Bay, New York

The Japanese delegation consisted of Jutaro Komura and Kogoro Takahira. Prior to the official start of the negotiations on July 27th, 1905 they visited President Roosevelt at his home in Oyster Bay, New York called Sagamore Hill. Roosevelt urged them to temper demanding reparations from Russian for the cost of the war. Considering themselves as victor, they felt entitled to indemnity from Russia. On August 4th Roosevelt met with the Russian delegation, Sergius Witte and Baron Roman Rosen, at Sagamore Hill. The Russians explained to Roosevelt, that they would continue the war if Japan did not drop their demands for compensation. Roosevelt remembered the meeting as unpleasant, particularly with his interactions with Witte. The President felt the talk had little chance of success yet urged them to continue as planned. The next day the delegations were introduced to each other by Roosevelt aboard the USS Mayflower in Oyster Bay. To avoid hierarchical problems inherent in seating arrangements there were no chairs present. With everyone standing Roosevelt made the following toast, requesting no reply to help maintain neutrality. “I drink to the welfare and prosperity of the sovereigns and people of the nations whose representatives have met one another on this ship. It is my most earnest hope and prayer, in the interest not only of these two great powers, but all of civilized mankind, that a just and lasting peace may speedily be concluded between them.” Immediately after the toast the delegations departed for Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The Russian delegation stayed aboard the USS Mayflower and the Japanese delegation boarded the USS Dolphin (Randall and Doleac Place, Part two). President Roosevelt returned home. The talks were agreed to be a direct negotiation between the nations, having organized the hosting of the talks and introducing the delegations to each other, Roosevelt’s official role in the peace talks was mainly complete. Third US Under Secretary of State Herbert Peirce represented Roosevelt in Portsmouth as host outside of all formal negotiations. Peirce coordinated with the Navy to conduct the hosting protocols (Randall and Doleac People, Part four). At the Portsmouth Navy yard additional telegraph lines were installed so Peirce could keep Roosevelt informed (Randall and Doleac People, Part four).

August 8th, 1905

In preparation of receiving the delegations the buildings of downtown Portsmouth were covered in stars and stripes bunting. Residence were asked not to display flags of Japan nor Russia to maintain an atmosphere of neutrality. Only 6 days prior 200 men began working nonstop to convert a naval store building into the negotiation headquarters (Randall and Doleac Hosts, Part one). The conference meeting room resemble the cabinet room at the White House, complete with mahogany and oriental rugs (Randall and Doleac Place, Part four). Seventy-six guns were fired to salute the arrival of the delegates in Portsmouth (Randall and Doleac Hosts, Part two). Komura told the press that he would give no interviews during the negotiations, conversely Witte was outgoing to the press and was quick to talk to journalists. He knew that Russia was seen as the losing side in the conflict and sought to turn public option (Randall and Doleac Hosts, Part four).

Thursday August 10th-12th, 1905

Formal negotiations began by Japan making 12 demands. The Russians replied two days later agreeing to two demands, indicated that they were open to discussion on six demands, and strongly disagreed with four demands. The four demands refused were: 1. Surrender of captures war ships. 2. Limitations on naval activities in the Far East. 3. Paying Japan’s cost of war. 4. Cession of Sakhalin Island, which was occupied by Japan late in the conflict after both sides had agreed to peace negotiations (Randall and Doleac Negotiations, Part 2). This was the island which Roosevelt suggested to Kaneko that Japan should occupy.

Sunday August 13th -17th 1905

After days of little progress at the negotiations table, both delegations attended church. Takahira inadvertently generated buzz after putting $5 in the collection plate (equivalent to $145 in 2020). After church Witte and Komura met in secret, walking through their hotel rose garden. They were able to mutually express their shared commitment to peace, alleviating much of the tension which had built over the early days of negotiations (Randall and Doleac Negotiations, Part 3).

At the suggestion of Roosevelt, the talks proceeded to focus on each demand individually, instead of debating them as whole (Randall and Doleac Negotiations, Part 2). Temporally putting aside the 4 demands with strong disagreement, they worked out the details the of the other 8 demands in succession. Building and maintaining a momentum in the peace talks. Over the next days, agreements were made at a fast pace. By Thursday there was agreement regarding Korea, Manchuria, Port Arthur, the South Manchurian Railway, and the Trans-Manchurian Railway (Randall and Doleac Negotiations, Part 3). The negotiation then turned into a heated debate regarding the four disputed demands. Witt refused to discuss indemnity nor Sakhalin Island anymore and suggested they move on to discussing fishing rights. Both Witte and Komura feared the talks were at an impasse and likely to end in failure. In a telegraph to Tsar Nicholas, Witte suggested they give up Sakhalin, particularly since the Japanese were in control of it. Komura telegraphed Tokyo and suggested they give up their demand on the capture ships and restrictions on the Russian Navy in the Far East (Randall and Doleac Negotiations, Part 4).

Friday August 18, 1905

The headline of the Portsmouth Herald read, “Crisis is Reached: Peace Negotiations May End at Any Moment”. In a private session with just the 4 delegates present, Komura floated the idea of dropping the demands of the interned ship and Russian naval restrictions if talks on Sakhalin Island and indemnity reopened. Witte said he had strict instructions on those issues, and that Russian would rather continue the war then relent. He then said that Russian would pay for the cost of care for Russian prisoners of war and asked if Komura would accept a portion of Sakhalin. Komura explained that Japan would not surrender Sakhalin but would sell half of it for 1,200 billion yen. Witte was doubtful Komura’s compromise would be approved but agreed to consult with St. Petersburg.

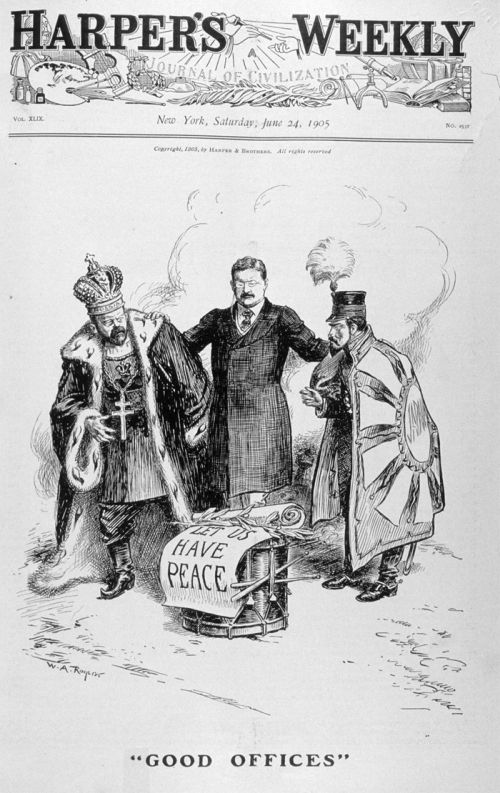

Meanwhile at Sagamore Hill in meeting with Kaneko, Roosevelt committed to use his “good offices” to resolve the deadlock. The next day Roosevelt met with Baron Rosen, a representative whom Witte had sent at the President’s request. The meeting was unproductive; Roosevelt then directed his efforts to the Japanese government and the Tsar directly with the use of back channel diplomacy and a flurry of telegraphs. Knowing that the German Emperor had influence with Tsar Nicholas, Roosevelt requested the Emperor to encourage the Tsar to compromise. He also contacted leaders in Britain and France to show their support for peace and conciliation. He had his Ambassador hand deliver a note to Nicholas, urging to accept the Japanese proposal and suggesting to not be too preoccupied on the amount of the indemnity as the specific amount could be worked out later. Roosevelt told Tokyo he supported Komura’s compromise on Sakhalin and suggested an indemnity of only 600 million yen (Randall and Doleac Negotiations, Part 4).

August 21st -28th, 1905

Delay, Delay, Delay

Monday’s formal meeting was postponed a day due to the previous meetings minutes not being ready. On Tuesday Witte received a telegram from the Tsar rejecting Komura’s proposal and ordered him to end the negotiations if Japan continued to demand land or money. Witte used his knowledge of Roosevelt’s continued efforts and meetings with Ambassador Meyers as justification to ignore the Tsar command. Tuesday’s formal meeting was postponed until Wednesday. On Wednesday, in a private meeting prior to the formal meeting, Komura again suggesting that Russian buy the northern half of Sakhalin and that all wording of indemnity be omitted. Witte asked if his proposal implied that if Japan kept the whole island there would be no request for money. Witte deftly framed Japan in the position of risking the promise of peace over money. Komura said no to the proposal and the discussion then reverted back to the established impasse where Japan insisting on payment and Russian refusing. With the whole peace talks in peril, Witte suggested that next formal session be delayed until Saturday the 26th, “Because an unexpected new situation has arisen.” Meanwhile in St. Petersburg, after another visit from Ambassador Meyer the Tsar agreed to give up the southern half of Sakhalin. Roosevelt continued to advise Tokyo to reevaluate their indemnity demand. On August 26th, Witte in another informal private meeting informed that Komura that no payment of any kind would be considered and that he was ending negotiations. Komura requested another delay for the formal meeting so he could get final instructions from Tokyo. The formal meeting was delayed until Monday (Randall and Doleac Negotiations, Part 5). The Japanese government amidst a series of meetings with their cabinet and military leaders, requested another postponement of the peace conference to Tuesday the 29th. On Monday, Tokyo instructed Komura to agree to peace and to try to keep half of Sakhalin. Late that evening, Witte received orders to end the negotiations; with four new Russian army divisions arriving in Manchuria via the Trans-Siberian Railway, Russia would continue the war. Witte’s reply to the orders stated that if he left Portsmouth without attending a final formal session, Russia would be blamed for continuing the war. He informed St. Petersburg that he would attend the formal session the next day and will not make any further concessions (Randall and Doleac Negotiations, Part 6).

Tuesday August 29th, 1905

Komura offered to drop the demand money if all of Sakhalin was ceded to Japan. Witte with orders to end the talks and make no more concessions said no. After a long pause, Komura offer to drop the indemnity if Russia gave up half of Komura. Witte agreed. By 12:30 the final details of the treaty were ironed out. Portsmouth Mayor William Marvin ordered the bells of the city to be rung from 4:00 – 4:030pm. Witte sent the news to Tsar Nicholas and was warily of his reply which he received the next day. It was a short statement instructing to only sign the treaty if it explicitly had the precise amount of payment for the cost of care of the prisoners of war (Randall and Doleac Peace, Part 1).

Noble Peace Prize

For his efforts culminating in Treaty of Portsmouth, President Theodore Roosevelt was awarded the Noble Peace Prize in 1906. Some critics have stated that Roosevelt was absent in Portsmouth and had little influence the negotiations (Tønnesson Controversies and criticisms). In reality, President Theodore Roosevelt initiated and organized the peace talks, his guidance to tackle each article of the treaty individually rather than as whole built the momentum that was needed to achieve success, his advice to occupy Sakhalin gave Japan a bargaining chip needed to solved what he understood as an improbable demand for indemnity, and his back channel efforts broke the impasse. His absence in Portsmouth was merely a physical absence and part of Roosevelt’s design. To alleviate concerns of foreign influence, the negotiations were direct between the nations without an intermediary present. When the direct negotiation almost failed, Roosevelt became the unofficial intermediary between nations as the delegations in Portsmouth stalled for time. Roosevelt also had an often-overlooked role with the naval strategy he shared with Japan. Without the overwhelming Japanese victory in the Battle Tsushima, instead of peace talks, the war would have been prolonged, possible pulling other nations into it and starting a World War.

Living Reminder

As a thank you for the role the United States play in the Treaty of Portsmouth, Tokyo Mayor Yukio Ozaki donated 3,000 cherry tree saplings to Washington DC (Fujisaki Washington’s cherry blossoms: A century-old connection between U.S., Japan).

Works Cited

Tønnesson, Øyvind. “Controversies and Criticisms.” NobelPrize.org, 29 June 2000, www.nobelprize.org/prizes/themes/controversies-and-criticisms.

“Russo-Japanese War.” Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 (11th ed.). 1911.

Randall , Peter, and Charles Doleac. “People, Part Three.” Portsmouth Peace Treaty, 1905-2005, Japan-America Society of New Hampshire, 2005, portsmouthpeacetreaty.org/process/people/people3.html.

Randall , Peter, and Charles Doleac. “Intro.” Portsmouth Peace Treaty, 1905-2005, Japan-America Society of New Hampshire, 2005, portsmouthpeacetreaty.org/process/index.html.

World of Warships. “Naval Legends: Battle of Tsushima | World of Warships” YouTube, 17 Jul. 2015, https://youtu.be/ink4S1adrhw.

Randall , Peter, and Charles Doleac. “War, Part 5.” Portsmouth Peace Treaty, 1905-2005, Japan-America Society of New Hampshire, 2005, portsmouthpeacetreaty.org/process/ war/war5.html.

Randall , Peter, and Charles Doleac. “War, Part 6.” Portsmouth Peace Treaty, 1905-2005, Japan-America Society of New Hampshire, 2005, portsmouthpeacetreaty.org/process/ war/war6.html.

Randall , Peter, and Charles Doleac. “Place, Part 2.” Portsmouth Peace Treaty, 1905-2005, Japan-America Society of New Hampshire, 2005, portsmouthpeacetreaty.org/process/ place/place2.html.

Randall , Peter, and Charles Doleac. “People, Part 4.” Portsmouth Peace Treaty, 1905-2005, Japan-America Society of New Hampshire, 2005, portsmouthpeacetreaty.org/process/ people/people4.html.

Randall , Peter, and Charles Doleac. “People, Part 4.” Portsmouth Peace Treaty, 1905-2005, Japan-America Society of New Hampshire, 2005, portsmouthpeacetreaty.org/process/ place/place4.html.

Randall , Peter, and Charles Doleac. “Hosts, Part 1.” Portsmouth Peace Treaty, 1905-2005, Japan-America Society of New Hampshire, 2005, portsmouthpeacetreaty.org/process/ hosts/hosts1.html.

Randall , Peter, and Charles Doleac. “Hosts, Part 2.” Portsmouth Peace Treaty, 1905-2005, Japan-America Society of New Hampshire, 2005, portsmouthpeacetreaty.org/process/ hosts/hosts2.html.

Randall , Peter, and Charles Doleac. “Hosts, Part 4.” Portsmouth Peace Treaty, 1905-2005, Japan-America Society of New Hampshire, 2005, portsmouthpeacetreaty.org/process/ hosts/hosts4.html.

Randall , Peter, and Charles Doleac. “Negotiations, Part 2.” Portsmouth Peace Treaty, 1905-2005, Japan-America Society of New Hampshire, 2005, portsmouthpeacetreaty.org/process/negotiations/negotiations 2.html.

Randall , Peter, and Charles Doleac. “Negotiations, Part 3.” Portsmouth Peace Treaty, 1905-2005, Japan-America Society of New Hampshire, 2005, portsmouthpeacetreaty.org/process/negotiations/negotiations 3.html.

Randall , Peter, and Charles Doleac. “Negotiations, Part 4.” Portsmouth Peace Treaty, 1905-2005, Japan-America Society of New Hampshire, 2005, portsmouthpeacetreaty.org/process/negotiations/negotiations 4.html.

Randall , Peter, and Charles Doleac. “Negotiations, Part 5.” Portsmouth Peace Treaty, 1905-2005, Japan-America Society of New Hampshire, 2005, portsmouthpeacetreaty.org/process/negotiations/negotiations 5.html.

Randall , Peter, and Charles Doleac. “Negotiations, Part 6.” Portsmouth Peace Treaty, 1905-2005, Japan-America Society of New Hampshire, 2005, portsmouthpeacetreaty.org/process/negotiations/negotiations 6.html.

Matsumura, Masayoshi. Nichi-Ro senso to Kaneko Kentaro: Koho gaiko no kenkyu. Shinyudo. ISBN 4-88033-010-8, translated by Ian Ruxton as Baron Kaneko and the Russo-Japanese War: A Study in the Public Diplomacy of Japan (2009) ISBN 978-0-557-11751-2

“Chapter 9 Roosevelt and Kaneko .” Heroes and Friends: behind the Scenes at the Treaty of Portsmouth, by Michiko Nakanishi, Peter Randall Pub, 2006, pp. 75-77.

“Chapter 11 Battle of Tsushima and End of War.” Heroes and Friends: behind the Scenes at the Treaty of Portsmouth, by Michiko Nakanishi, Peter Randall Pub, 2006, pp. 84.

Hughes, Wayne P. (2000). Fleet tactics and coastal combat. Naval Institute Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-55750-392-3.

G. Patrick March (1996). Eastern Destiny: Russia in Asia and the North Pacific. Praeger/Greenwood. ISBN 0-275-95566-4.

Fujisaki, Ichiro. “Washington’s Cherry Blossoms: A Century-Old Connection between U.S., Japan.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 20 Jan. 2012, www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/washingtons-cherry-blossoms-a-century-old-connection-between-us-japan/2012/01/13/gIQAD2XmEQ_story.html?noredirect=on.